The Japan Society invited me to review The Japanese House, Since 1945 – by Naomi Pollock, these are my impressions.

In recent years the unique work of Japanese architects has been explored and memorialised in a seemingly endless stream of coffee table books. The conversation in these is invariably reduced to the level of a beauty contest and in providing further evidence of just how “other” Japan is.

Like Instagram they are meant to be flicked through rather than read.

However, The Japanese House Since 1945 is a large format 400 page book and like its excellent predecessor Japanese Design Since 1945 is thoroughly researched by Naomi Pollock and beautifully produced by Thames and Hudson.

Pollock takes us on a journey from the 1940s – Rising from the Rubble, to the 2020s – Pandemic Panic. Each of these chapters begins with a brief sketch of the period highlighting key events such as the post-war housing shortage in the 1950s, or the Fukushima earthquake and tsunami in the early 2020s. By explaining the economic, social and political context of these periods she helps us to understand the design of the houses beyond that of the beauty contest.

Where this book is different to others is in Pollock’s goal to convey what it’s like to live in these houses. To achieve this, the two most interesting aspects, in my opinion, of this book are firstly the ‘At home’ resident’s autobiographical descriptions of day-to-day life in these houses. For example in At Home Tower House, Azuma Rie says :

‘When our family moved to Tower House, which was designed by my father, Takamitsu Azuma, I was still in elementary school. On the first day, we kept our shoes on because the floor was not yet finished – it was just a rough concrete surface. This was unusual because Japanese people normally take their shoes off at home…’ (p. 123)

And secondly the ‘Spotlight’ sections which describe in detail a specific feature unique to Japanese architecture. For example – The Site, Walls and Doors and Gardens & Courtyards. As we work through the examples from the 1940s to the 2000s, we can see how these features have been integrated and adapted as fashion and howmaterials and design have changed. For example in The Window Pollock says:

‘Another consideration is placement. Western-style windows are often situated at eye level for those seated on chairs. But in Japan, a country with a long-standing habit of floor-sitting, windows can be located up high as well as down low. Even in rooms with upholstered furnishings, window positions are calculated to edit the view without severing the connection to outdoors.’ (p. 219)

I found these insights to be a great way of understanding the building constraints and cultural precedents the architects were trying to navigate while designing homes for their clients and families.

I’ll be honest I am not in the habit of reading introductions, but this time I am glad I did as Pollock puts the reasons (not all happy) the Japanese have been able to build such unique houses into context. She explains that the end of the war in 1945, for reasons we all understand, was a point of reset for Japanese society, architecture, and house building. From this time a fundamental re-think of what a house could and should be was both necessary and possible.

In the shadow of Japan’s wartime defeat, western models of contemporary living became desirable. All aspects of life were reconsidered, such as the promotion of the nuclear family (parents and children) rather than the traditional multi-generational family, alongside the separation of eating and sleeping which had previously taken place in the same room but was now considered unhygienic.

Before that moment, Japanese architects were being influenced by European modernism, so by the time Japan had seen widespread bombing and devastation of its big cities and new houses were needed, architects were free to create unique expressions of the Japanese home along modernist lines. It was a clean slate for the architects against a sad backdrop for the average Japanese.

Due to Japan’s geographic location, the risk of earthquakes, and the fires which inevitably follow, party walls in wooden houses are very rare in Japan. A fire gap is necessary to separate each house, which in turn, allows them to be created like an individual object. In other words, they don’t have to relate, visually or in personality, to the house next door. This gives the architect a freedom unimaginable in a city like London. Alongside this visual freedom is the ability and desire to experiment with materials and formats which integrate or not with the environment.

On reading this it makes total sense of my own experiences. On my many nocturnal photographic excursions around Japan’s cities and big towns, I have always been fascinated by the freedom Japanese architects have to express themselves with little or no regard for their neighbours. And then, seemingly overnight pull them down and start again.

What I haven’t mentioned is the more than sixty incredible houses this book introduces to us.

There are twenty or so that I love! but if I am forced to pick out a few personal favourites, it would be the early modernist houses of the 1940s. Such as the enigmatically named House no.1 (p.32) by Ikebe Kiyoshi, built in 1948. This is a lovely example of a largely wooden (before the blight of concrete houses) paired down home, responding to a shortage of materials and a quest for a new way of living post war.

And then I am drawn to the distinctly contemporary Japanese colour palette of Our House (p. 171) by Hayashi Masako and Hayashi Shoji built in 1978. The red stained walls and wooden eaves of the deeply pitched roof creates a dramatic space which feel at once like a modern and traditional Japanese home. Add to this the huge sliding shoji-style window revealing a stunningly peaceful walled garden, I could move in tomorrow.

If, like me, you spend too much time scrolling through Japanese architecture and design feeds on Instagram, are obsessed with house remodelling programs on TV or have a professional interest in Japan, you will find this book chronicling Japanese house architecture fascinating.

I recommend you buy it and read it, don’t just leave on your coffee table.

Review by David Tonge, for The Japan Society

RELATED

-

At your Convenience

Just what, I hear you ask, is the magnetic pull of the Japanese Convenience store or Konbini as they are known ?

-

Pictures of Japan

Japanese bathroom ceramic ware maker TOTO invited me to curate a small collection of these photographs for their 100th year anniversary during Clerkenwell Design Week in London.

-

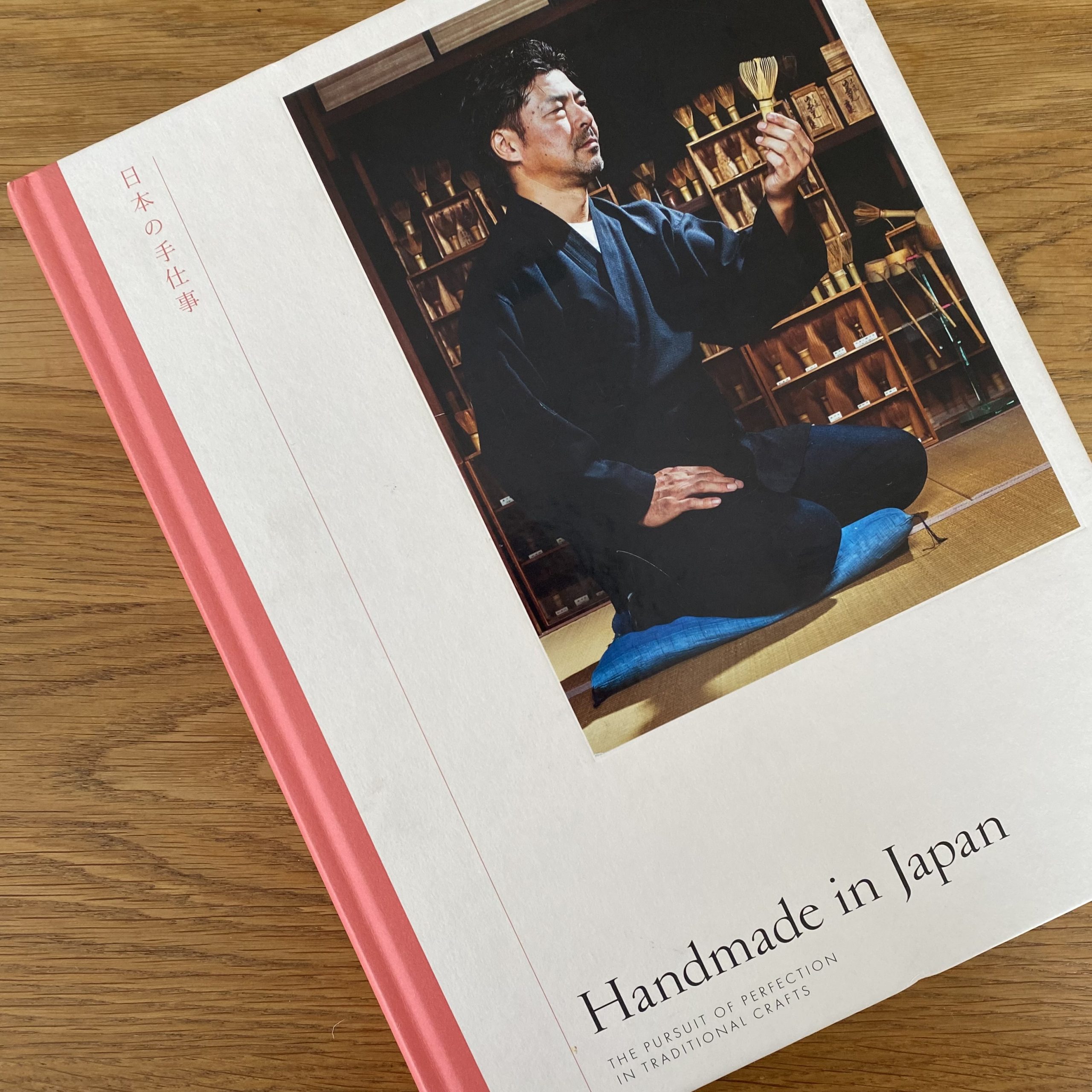

Handmade in Japan

If like me you have an appetite for exploring all things related to Japanese design and crafts, Irwin Wong’s introduction to Handmade in Japan will surely prompt you to investigate further